Japanimation Station: A System for Digital Archiving Analog Media and More

by dasseclab

This should be a fun little detour from what would be my normal blatherings about network engineering or network security.

Background

In an age of numerous streaming services that cater to general audiences, smaller services that cater to niche programming or large platforms like YouTube that split the difference between corporate mass media, independent “content creators” and totally random everyperson with a camera and modicum of editing software, one might wonder, why even care about analog media? But if you look through the video section hosted by the Internet Archive, you’ll see digitized renderings of analog media abound. There are several reasons for this - some are related to the physical media themselves, some to the content on media. Not all items released on physical home media on video cassette or LaserDisc made a transition to a digital format like DVD or BluRay. In some cases, films may be re-cut over several releases: Blade Runner for instance was notorious for having multiple director’s cuts released on home video. A franchise like Star Wars also famously went through modifications on re-releases of the original trilogy. Amongst film afficiandos and deep-diving fan folks, these different versions are sought after as each version has its own story to tell. Other folks are interested in recordings from television broadcasts, using those pesky commercials like some sort of time capsule.

I am over-explaining a lot here as far as technology for any potential younger readers. No offense intended for folks who lived through or understand home video in the 1990s and very early 2000s.

I spent the majority of the 1990s getting deep into Japanese animation (anime, or once poularized “Japanimation”) fandom. During that time, VHS was the most dominant consumer home video format and with a VCR, one could record programming off of television broadcasts. Video cassettes released commercially usually came in one format or another - Japanese language with subtitles or Dubbed in English (in my case in the US). If you read through Usenet’s rec.arts.anime at the time, you can see that there was a heated debate about which was “better” or who the “real fans were”. This isn’t a post to re-hash any of that. Anime fandom has a deep DIY undercurrent that led to the development of unauthorized translations, edited onto tape using PCs and copied for limited distribution, known as fansubbing. If you belonged to an anime club of some sort or knew the right people, or had access to Asian-town markets or could surf the WWW, you could get access to some of these subs. Fansubs were typically reserved for anime that wasn’t commercially available for a variety of reasons. Within fan circles now, there is a value in both nostalgia and historical preservation for these fansubs, often times co-existing along with authorized commercial releases. Like other mainstream films and television, anime that is re-released on more current formats (streaming or physical), might include a new dub or new translation though there might be some nostalgic attachment to the previous version.

There is more than simple nostalgia of my own teenage and university years though; there’s a more practical concern with physical space. LaserDiscs get heavy and my tapes simply take up a lot of room. Digitizing this media means I can streamline the amount of stuff I am storing, preserve and share items with others if wanted and maybe offload tapes and discs to other fans with more room. That’s quite an involved user story.

Use Case

Included with the reasons of personal nostalgia and archiving for other members of the fandom highlighted in the background section, there are additional technical limitations to analog media. The storage media of video cassettes is magnetic tape which are sensitive to heat in storage. For any lengthy period of storage, they need to be kept in a climate controlled area in order for the tape to remain readable. Additionally, the signal on the tape suffers some minor degree of loss with each playback. Given that some of these tapes were a part of a hobby and in some instances, the only way to watch these shows, I played these tapes a lot back in the day. Tape quality matters and cost always a factor (especially a teenager’s hobby), sometimes corners were cut on tape quality. More corners were cut with recording speeds. In the days of my heaviest usage, VHS VCRs recorded in 3 speeds: Standard Play (SP), Long Play (LP) and Extended Play (EP). On a standard VHS cassette (T-120), SP was 120 minutes (2h) of recording time. However, quality of the recording could be sacrified to get more recording time out of that same cassette. LP was 4 hours and EP was 6 hours on a T-120 cassette. There were other cassette types that could get as much as 10 hours on EP. At one point, my personal standard was Sony V T-180s, which could do 8 hours on EP and 3 hours SP. Finally, there was loss when you recorded tape to tape. This was very important when it came to fansub tapes. It could be noticable loss, too, the further number of copies you got away from a primary recording.

LaserDisc, unlike video cassette, was stored on a pressed optical media (disc), not too dissimilar to a compact disc (CD). It was also not a medium a consumer could record onto at home so the vast majority of LaserDiscs in circulation are commercial products. Like CDs and other optical storage, LDs are vulnerable to scratching, extreme light exposure, warping and other physical damage to the platter that will make it more difficult for the LaserDisc player’s laser to read data from the disc. Additionally, almost unique to LaserDiscs, is the risk of Laser Rot, where a layer within the disc oxidizes and renders the disc unplayable. We compound these with the fact that in North America, LaserDisc was an enthusiast format, so titles vary in availability and players are harder to come by. Fortunately for the anime fan, LaserDisc was more popular in Japan so there are quite a few Japanese cartoons on LD, if one can tolerate the lack of subtitles or translations.

System Design

Our minimum product for this problem is a method or system in which we can capture the output of an analog signal into a digital format. Once digitized, I would need to be able to utilize at least a basic video editing suite to make adjustments to the captured video, such as cutting large captures into individual files or touching up video that was noisy with static. A stretch goal for this project would be something that I could do more complex editing on, such as complete video correction for very poor source tapes or adding in subtitle tracks to videos not already in English. If I’m really adventerous, I’d maybe look into authoring higher definition touch ups. Though this is routine for professionals, as a amateur hobbyist, this is still a daunting idea and not yet in scope for this design. The system would also utilize Free or Open Source Software (F/OSS) as a matter of principle as well as comfort. As I’d not really built a PC in quite some time, re-using under-utilized hardware wasn’t really an option for the digital side of the system.

On the analog side, we have different hardware for playback of different media - chiefly VCR for video cassette and LaserDisc Player for LaserDiscs. Both sets of hardware operate over a universal standard of RCA component. The RCA jacks on each player will be connected by RCA plugs into a device by which the analog electrical signal can be received and converted to a digital signal. In a perfect world, multiple RCA component jacks would be able to be connected to multiple RCA plugs and signal could be toggled by either software (capture selection) or hardware (dip switches) but this is would stray into pro-am territory on the low end of cost or require professional equipment, thus higher cost. As this project is much more amateur than professional, I settled for a single set of jacks and physically toggling the plugs for different players when I wanted to change input.

The Alternatives Considered section will have some detail to, well, alternatives at how I arrived at this design. What I wound up executing as the final design was iterated over a couple of concepts.

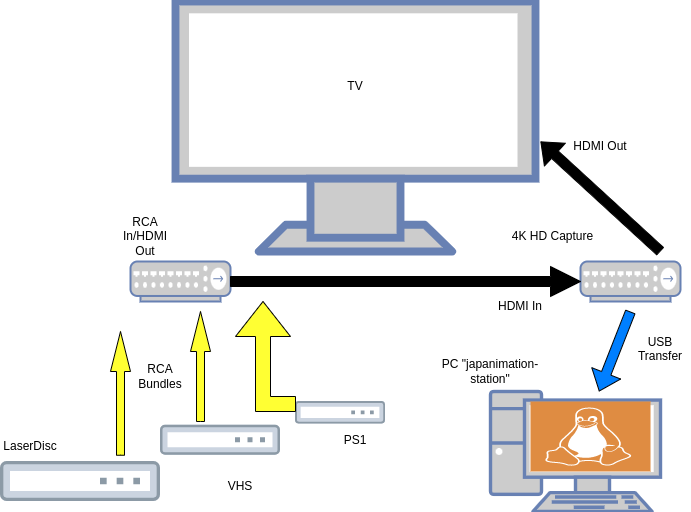

(Ok, as a network engineer, I would be remiss not to include a schematic of some sort.)

As we can see in the schematic above, our analog playback devices transmit a signal over the RCA component coaxial cables to a digital converter device. Each playback device is cabled independently, bundled together by velcro for cleaner cable management, but must be physically manipulated if we want to change analog input device. The digital converter is unidirectional in that it receives analog input and generates a digital output. If constructing one’s own system based on this design, pay close attention as there are other unidirectional devices that work in the opposite direction and can be a fraction of the cost. The digital converter outputs its digital signal utilizing High Definition Multimedia Interface (HDMI). Once converted, the digital signal is transmitted to a 4K UHD capture device via HDMI cable. The capture device has two output interfaces; one HDMI to route to a monitor or television and another USB for pick-up by PC. The monitor/television output provides a method to perform live feedback and verifying the analog to digital signal conversion. When the capture is read on the PC, it can be recorded by software and the recording can be exported to standardized video encoding formats, such as MP4. From there, the file acts as any other digital video file and can be manipulated for subtitling or other forms of editing.

There are a couple of drawbacks to this design. The first is that captuing the video is limited by the real-time playback of the originating analog media - a 90 minute film takes 90 minutes to record. With hundreds of hours of video to record within my own collection, getting every tape and disc recorded takes some degree of planning. However, the benefits of such a design outweigh this drawback, particularly as a hobbyist project. By utilizing a 4K UHD capture device, I am obtaining prime captures of this media. These are, essentially, the best they will look from these sources. Additionally, while appearing more complex, using a separate capturing device offloads processing requirements from a PC’s CPU and enables “lower end” PCs to be able to perform this task (more on that when we get into the hardware components used). The second is that the analog to digital converter does require some reboots to maintain audio video synchronization. As the converter requires independent power, this is accomplished through periodic reboots, particularly if there has not been capturing done lately. Since this is a hobbyist project and not presented as an enterprise solution with high availability or redundancy required periodic reboots that lasted under 1 minute are an acceptable trade-off.

Proof is in execution though. During initial testing of this set up, I performed this capture of a LaserDisc and tweeted the results here. The clip, even modified from its original length and under social media and content devlivery conversions, still looks pretty good. I had my own belief in this capture method and was validated by some on Twitter but often times independent validation is helpful. For the YouTube generation, I stumbled upon this channel recently but just saw this video they produced the other day (even while I was halfway through drafting this) and they independently verified this method as their preferred method of capture. While our individual components may vary (for a variety of resons only speculated upon), the overall system designs remain consistent. And seeing someone who presents doing a sizable number of conversions using the same method as the “highest quality”, does give me some degree of confidence.

Alternatives Considered

This is actually my second foray into attempting to digitize my analog media. The first attempt was in the very early 2000s when I was headed off to University. As noted in the introductory sections, much of this media was from a hobby I was into in the 90s as a teenager, which, if enterprising, can result in quite a collection. At the prospect of moving away to University, the thought of lugging a whole bunch of VHS tapes with me seemed very inefficient and like a waste of space, especially as I was moving into new dorms of which I’d only seen pictures. I purchased a TV Tuner card with a coaxial input, which I could connect my VCR’s co-ax output, and installed it into my PC. A week or so of trying to get it to work with incomplete instructions, I wasn’t successful with any good captures. Like this system, playback time being a chief limiter, I was on a tighter schedule even if I could pick and choose the titles I wanted digitzed most to show off to future friends and colleagues. The tuner card was returned and I eventually wound up schlepping tapes around.

Approaching this problem recently, I figured that TV Tuner cards would come about again, And knowing that I would be in for another new PC to perform all of the editing I needed, I figured I would need expanded independent video card solutions as well. The first design was a purpose built PC with an independent drive for operating system functionality and plenty of swap space for the CPU and RAM as well as additional disk drives for data partitions, a PCIe video card for rendering video edits and another PCIe TV Tuner card. In the interim, I did have the foresight to ask others within the same hobby and age brackets what they were using, if they were digitizing their analog media.

I was pointed to the Hauppauge RCA-USB converters. These are converters with RCA jacks that convert analog signals to digital and exported via USB to a PC. Unlike the design I wound up going with, the capture feature set needs to be performed by the PC that is connected to the device via USB. With the independent capture device, the PC only approaches 20% CPU utilization during a recording, which is sustained even over a number of hours during the duration of a recording. While simple, I would expect including the capture+recording rendering of a similar CPU chipset to increase significantly which can have negative effects on the presentation of the capture media. The Hauppauge converters are cheaper now though when I was first pointed to them, they were not that much more expensive. The system utilized is more expensive than the option I wound up going with but the cost sacrifice is in the name of performance.

Components

In this section, I will detail the compoents involved in this system and what each represents. I’ve separated the hardware from the software components that others may substitute specific compoents to their own needs.

Hardware

The hardware is composed of the analog players at the origin end, an analog-to-digital converter, a capture device then terminating to a PC for recording.

Analog playback is performed by hardware devices dependent on the storage medium - LaserDisc or VHS format video cassette. For LaserDisc, I am using a Pioneer CLD-D501. For video cassettes, I am using a Panasonic PV-7451 VCR. In the future, I may upgrade the VCR to another model as I have had this Panasonic since 1996 or 1997 and used it for a lot of fansub duplication. Perhaps an S-VHS VCR…

The terminating PC is a refurbished (hence, cheaper) Lenovo ThinkCentre M92 with an Intel i5 CPU and 16GB of RAM. I chose the specifications for a number of reasons:

- Intel’s i5 chipset is a good, middle range CPU which can handle video editing and performance.

- 16GB, at time of writing, is still capable enough to render high quality video for editing and processing, especially if purpose built for those functions.

- Lenovo, despite reputational cost of its former IBM hardware lines, still functions very well with Linux.

- Refurbished not only reduced personal financial cost but also stress and time overhead of assembling and testing a new PC.

- The form factor of this model met the physical space and storage requirements.

There are caveats to the terminating PC design. While it holds true that Lenovo Think- lines functions very well with Linux, the age of the M92 ThinkCentre apparently puts it in a weird spot with onboard Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs), a computer security measure for cryptographic signatures of firmware and software. The M92 specifically includes hardcoded firmare looking for Microsoft Windows in its boot records. If you are using this PC with the refurbisher’s licensed Windows installation, as was delivered to me, this is seamless and there are no problems. However, if you want to utilize another operating system, like Linux, that requires a different boot manager, like grub, then you have to make several manual tweaks to the BIOS and firmware settings. I detailed this here both for helping other M92 owners/recipients and for myself, in case I ever got into the mess where I needed to do a clean install and was once again greeted with the 1962: Operating System Not Found error again.

Conversion & Capture

To convert the analog signal to digital, I use the “ONN. Composite AV to HDMI Converter”. This converter is powered by a wall outlet to Micro-USB and features a hardware toggle switch for conversion to either 720p or 1080p standards output. Deisgned origionally as a means for additional RCA component connectors for televisions or monitors which have few to no RCA component jacks, transmitting an HDMI signal out means it can pass through other HDMI hops with no (or very close to no) signal degredation. Like mentioned before, this device is unidirectional so it will only accept analog in to digital out. If you are looking for something that will take a digital signal in and convert it to analog out, that is a separate device.

For capturing the HDMI output of the converter, I opted for this 4K UHD Audio Video Capture Card. It is powered by the same USB 3.0 connection that it uses for data transfer to a terminating PC. With the rise in popularity of Internet/digital streaming like Twitch, there are several manufacturers making similar capture devices. This card has an HDMI input for source video and audio input, as well as a separate 3.5mm microphone jack for additional audio overlay if desired. It outputs over USB 3.0 to a recording PC and HDMI simultaneously for playback verification.

Storage

As archiving is the expressed purpose of making these analog to digital conversions, I need to talk about the storage options for this system. Internal disk storage for the system is a 500GB SSD, which is plenty of space for the operating system and ample space for our digital recordings. I’ll get into file structure a bit in the Software section below but suffice to say, since I am recording whole tapes have multiple episodes on it, even possibly a variety of programs, I’ll need to edit those first digital recordings to smaller files. And let’s face it, in this sense, I’m not going to discard the raw capture files either on the off chance in the future I can better encode them or clean them up. As I never really did any video editing on spinning hard disk drives, I imagine that the caching, block searching and input/output (I/O) advantages one gets with a solid state drive are beneficial to the recording and rendering of video.

But the internal storage isn’t all there is. I’ve also gotten a couple of 8TB SATA hard disk drives to use as external storage. I’ve not fully come around as to whether these will be individual drives or if they’ll get added to a Network-Attached Storage(NAS) array. In either scenario, the data stored on these external storage drives will be for colder storage that will be accessed less frequently.

Our final storage endeavor will also be writing to Blu Ray optical disc via an external burner. Writing to opical disc is an additional redundancy of cold storage to mitigate the potential failures of either SSDs or HDDs and the 25GB capacity of individual discs will typically hold a “full archive” (raw source recording+edited files). As burn jobs can be repeated, additonal redundancy can be achieved by writing to multiple discs.

Software

My preference is to build using Free or Open Source Software (F/OSS) as possible. I opted for Kubuntu LTS because Kubuntu has a modern operating system feel and it’s long term support cycle leaves few surprises. The filesystem is ext4 as it can handle large file sizes (up to 16TiB) and has a long history of support within Linux environments. I’ve organized the directory structure within ~/Videos as an assembly line structure - new captures get sorted by sources, then when those files are edited, they go into an edit directory and once things are finished up, they all get moved to an archive directory to be copied over to a different storage medium.

For playback on a PC for quality check, I am using VLC Media Player for it’s availability across platforms and wide array of codec support. I still shudder at the early 2000s and not just the variety of video formats (several still with us) but the variety of video codec packages that predated the Combined Community Codec Pack (CCCP) which almost guaranteed no two players would play the same video. Perhaps unfounded in 2023 but those scars are deep.

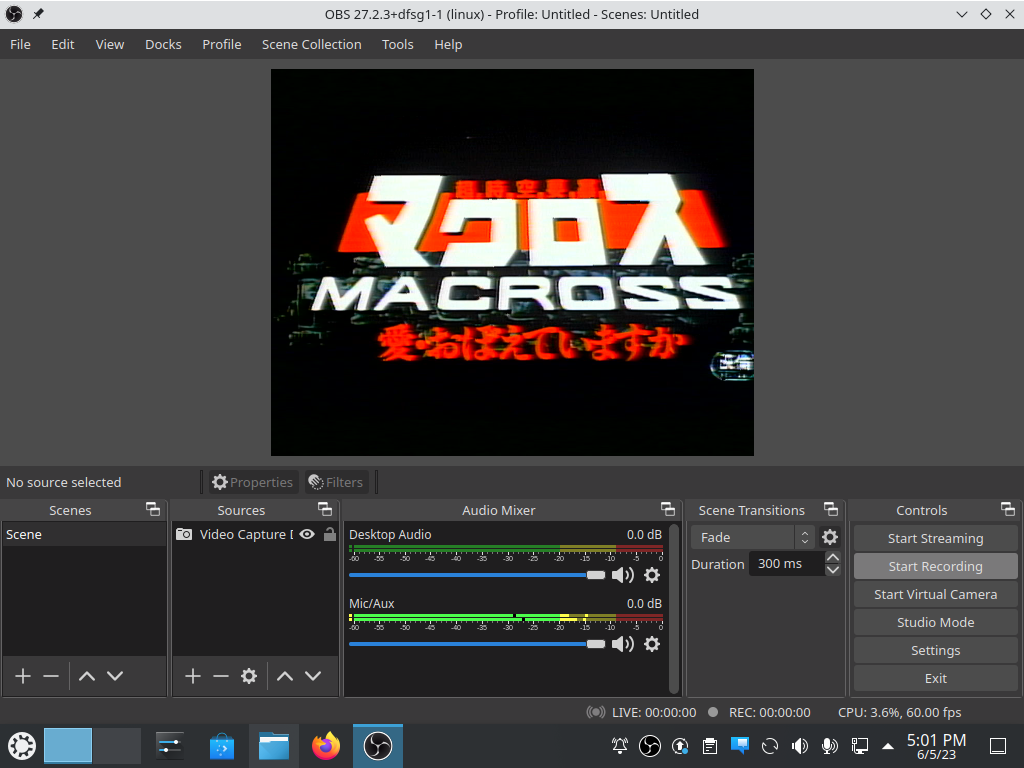

Capture

The signal that is transmitted by the 4K UHD Capture Device is recorded using OBS Studio, where the recorded file is exported to MP4, which I use becuase of it’s wide array of device support, including directly by most modern televisions. The recommendation for OBS came directly from the Capture Device instructions and it was fortunately natively included in Kubuntu’s base repository. As this Capture Device is popular with video streamers, there are probably other pieces of software that can accomplish this task but there being a native Linux version and frictionless install, I went with this. The initial configuration was fairly straightforward and I have not noticed a need to make any alternate configurations for different sources.

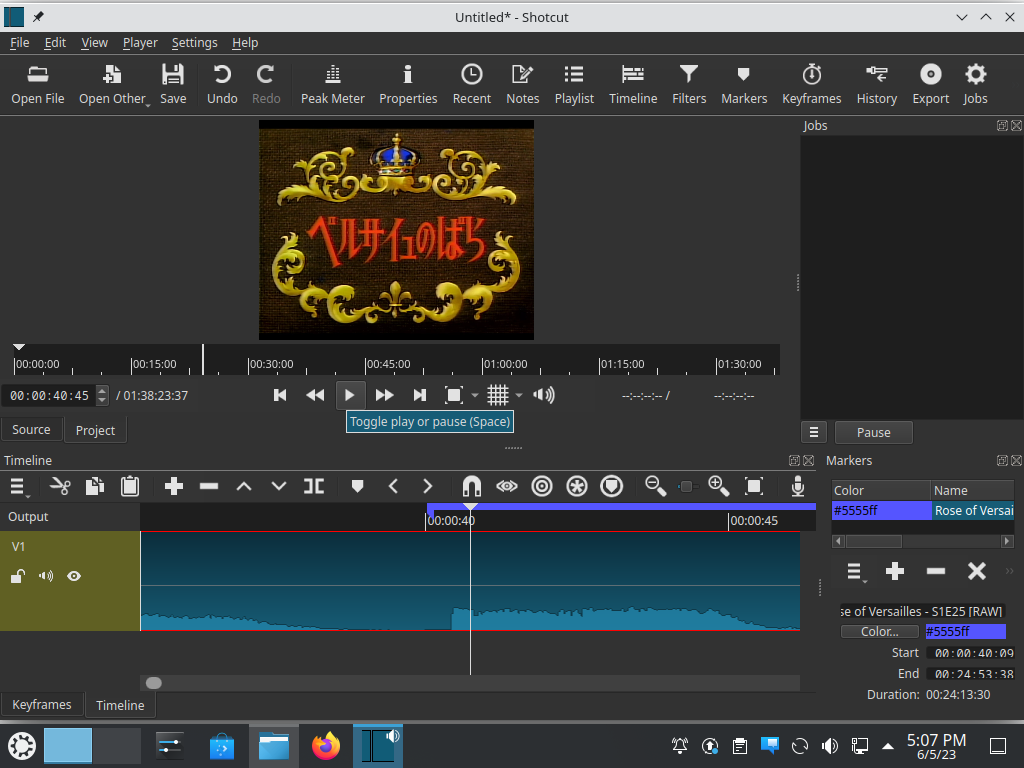

Editing

Once recorded, it comes time to edit. I mostly wanted a lightweight editor as the bulk of editing are simpler cuts - trim some edges of VCR or LD play screens, remove the frames where the LD player’s laser rotates when the disc is finished playing that side (or the time it takes for me to manually swap discs for anything greater than 60 minutes of runtime), segment episodes or cut commercials into unique files - but hopefully powerful enough that if I wanted to learn some restoration techniques it might be capable of handling those. So far, I have been using Shotcut to fullfill most of the needs I have found so far. As I am truly an amateur at video editing in any sense of the word, I have not really found the ability yet to get to the restoration projects but for every other usecase, Shotcut checks all of the boxes. Support for Shotcut has been refreshing. Certainly not as widespread as competitive commercial software like Adobe Premier, once I figure out the right terms, there are usually a handful of tutorials to demonstrate what I need.

Subtitling

While sorting out video restoration, I’ve decided to also get a little adventurous and do some custom subtitling as well. The first couple of projects I’ve identified for subtitling are creating English translations for some non-English language programming. Writing the translated text will be in some native text editor but in order to do the script timing and overlay, I’m using the tried-and-true Aegisub, used by pros and hobbyists alike. A multiplatform OSS package, it can be installed on Kubuntu using snap as opposed to the traditional apt.

What’s Next

This is a home lab project that was intended to solve one problem - conserving physical space by digitizing analog media but has the potential to fulfill a few other hobbyist needs or side projects. The obvious thing first and foremost is to explore the potential to do this work for other fans or hobbyists. The first milestone is to get some of the material I’ve recorded out into the hands of others for review. If the reviews are favorable, I would open up to other fans sending me their media and I could make the conversions and return the original media with digital copies (if they are interested in such a thing to begin with in the first place). But this feedback is also good to iterate on the capture process or editing techniques to make better captures.

Other future projects would be more subtitling endeavors. I don’t think I will ever get to the point of being a fansubber of full series or films, as fansubbing iteslf is very time-consuming and laborious but perhaps small clips or commercials for various talks at hobbyist conferences. It is a longer term goal, and certainly not one I had at the outset of this project, so I will see how much of a stretch goal this becomes when I finish the couple of things that I truly want to sub now.

The final item in the next stage would be finding reasoable-cost hosting for making some of these archives available to others who are interested. The Internet Archive may be it. Hosting via Google Drive or AWS S3 may cause interruptions to service if there is a misunderstanding. YouTube, while one of the most popular video sharing services, reportedly sees archivist content as hard to monitize. Other, smaller platforms like DailyMotion or Vimeo may not have this problem but don’t have a “reach”. This is a complex problem in a space I’m still not the most familiar with, unlike “tape this for me” by mail or creating a fansub, it’s a further target to hit.